Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

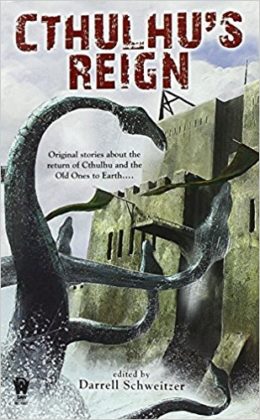

Today we’re looking at John Langan’s “The Shallows,” first published in 2010 in Cthulhu’s Reign. Spoilers ahead.

“The vast rectangle that occupied the space where his neighbor’s green-sided house had stood, as well as everything to either side of it, dimmed, then filled with the rich blue of the tropical sky.”

Summary

Over his daily mug of instant coffee, Ransom chats with his sole companion, the crab resident in his kitchen sink. “Crab” may just be a convenient label for the creature, which with its extra set of carapace-top limbs is no earthly decapod. Thirty yards to one side of Ransom’s house, where his neighbor’s house used to be, ripples a curtain of pale light extending as far as he can see. At the moment it displays a tropical sea seething like a pot about to boil. Fish, whales, sharks flee the center of the disturbance. Among them are beasts beyond identification, “a forest of black needles, a mass of rubbery pink tubes, the crested dome of what might be a head the size of a bus.” An undersea mountain rises, or is it the top of a vast alien Atlantis? The first time Ransom watched this “movie,” he and his son Matt wondered if the upheaval had anything to do with “what’s been happening at the poles.”

Ransom suggests that he should name the crab “Gus,” after his wife Heather’s great-grandfather. Once they thought of naming their son after Gus, but from all accounts, he was an abusive alcoholic so mean he wouldn’t take in his war-disabled son. You know, Jan, whom the old man called a “faggot” because he liked to bake.

Though Ransom’s looked away from the light-curtain, he knows what it must be showing now: a vast entity of coil-wreathed head, scaled limbs, translucent fans of wings, bursting from the risen city. It’s a thing whose sheer size and speed must “break a textbook’s worth of physical laws.” The first time he watched its rebirth, Matt had screamed “Was that real? Is that happening?”

Ransom prepares to leave the house, picking up an improvised spear (butcher’s knife duct-taped to a pole) and making a careful survey of the front yard before opening the door. Before going north two months earlier, Matt made him promise to perform the safety check every time. Nothing worrying, except the ruins across the street and the spongy hive that they once sheltered. Lobster-like things the size of ponies may have hatched from it. Matt led the neighbors who dispatched them with axes, shovels, picks. Northward, everything’s gone, road, houses, vegetation, the ground scraped down to gray bedrock. On the horizon more planes of light shimmer.

Spear at the ready, Ransom exits his house. He’s going to his garden and invites the crab to come along, which it does with eager speed. Ransom, Matt and neighbors tilled the garden together, fenced it, and dug a moat-trench around it. The crab scuttles among the carrots, broccoli, tomatoes, inspecting the plants with such intensity that Ransom’s sure that “in whatever strange place it had called home, the crab had tended a garden of its own.” He speculates aloud about calling the crab “Bruce,” which was the name Heather gave a stray dog she took in late in her struggle with terminal illness. The dog had comforted her and Matt but not for long. Its loutish owner reclaimed it five days later, locked it again in a wire pen. Heather visited the caged Bruce, from the safe distance of the road, right up to her final hospitalization.

In the garden, big red slugs threaten the lettuce. Ransom drowns them, like ordinary slugs, in beer traps. A huge blue centipede crosses his path. He doesn’t spear it, for fear it may “control” other invaders. Inky coils have attacked the beans. Inky coils with teeth. Ransom burns the affected plant and considers whether the neighboring plants can be salvaged. Fresh food’s nice, but the neighbors who went in search of the polar city with Matt did leave Ransom their stores for safe keeping.

The light-curtain beside his house begins to play another movie, featuring a cyclopean structure at sunset. Ransom’s seen this “movie” before, too, and has identified the structure as the Empire State Plaza in Albany, fifty miles north of his town. Its office buildings are decapitated. A massive toad-like being perches on the highest skyscraper. Far below, three figures flee from black torrents that sprout eyes all along their lengths and open tunnel-wide sharp-toothed mouths.

Ransom begged Matt not to go north. Who could tell what the inhabitants of the polar city would do to him? And who will Ransom talk to, without his son? Matt told Ransom to write his experiences all down, for when Matt returned. But Matt won’t be coming back. Matt’s one of the three figures the torrents devour, as the light-curtain shows Ransom over and over again.

The crab has scuttled to the top of the garden to inspect some apple trees. Ransom only glances at them. They appear to be “quiet.”

He and the crab return home. Ransom tells it that Matt used to say, “Who wants to stay in the shallows their whole life?” Ransom’s answer, which he himself hadn’t fully understood at the time, was “There are sharks in the shallows, too.”

Back at the top of the garden, the apples swing in the breeze and ripen into “red replicas of Matt’s face, his eyes squeezed shut, his mouth stretched in a scream of unbearable pain.”

What’s Cyclopean: The beans in Ransom’s garden are full of “gelid, inky coils.” Those things are almost as bad as Dutch Elm Disease.

The Degenerate Dutch: Gus, for whom Ransom’s sorta-crab (but not his kid) is named, appears to have been a bundle of delightful bigotries.

Mythos Making: R’lyeh rises and Cthulhu rises with it, heralded by shoggothim. The toadlike thing is probably Tsathoggua…

Libronomicon: No books this week. Where are those million copies of the Necronomicon when you really need them?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Gus (the person, not the sorta-crab) was a “functioning alcoholic” and an abusive jerk.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I used to love end-of-the-world stories. It was a way of coping with the last days of the Cold War, imagining that stories could still take place Afterward. And there can be comfort in an apocalypse that grinds away the stress of daily demands and narrows your choices to those that are truly important. I especially liked the so-called cozy catastrophe, in which survivors crawl out of their shelters in neat family units to rebuild the world better than it was before, or at least closer to the author’s preferred societal organization.

Langan’s catastrophe is anything but cozy. The neat family unit’s been broken up in favor of a last-ditch save-the-world effort, failed almost before it began. And—cozy inevitably being a matter of point of view—the story’s from the point of view of the last-ditch save-the-world hero’s aging father. Nothing like parenthood to remove any last vestiges of comfort that an apocalypse might otherwise have retained.

The rise of the elder gods makes an excellent stand-in for all manner of apocalypses. (Apocalypsi? Apocalyptim? This is becoming an increasingly urgent question, folks, help me out.) Charlie Stross memorably hybridized it with the devastation of nuclear war, and in his more recent work it’s metamorphosized to cover climate change (Case Nightmare Green turns out not to be an event, but a stage of earth’s history with no end in sight) and the rise of fascism. In Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald,” it’s more like colonialism; in Drake’s “Than Curse the Darkness,” it’s a price for the overthrow of same that just might be worth paying.

In “The Shallows,” the apocalypse in question might be the plain everyday one of mortality. Eaten by a shoggoth or consumed by cancer, Matt and Heather both die. They both go down fighting for life—Matt for the world, Heather for an abused dog—and neither succeeds. Just like in real life, too, there are screens everywhere to show you the details of every ongoing disaster, over and over and over and over. Who knew that elder gods were so into mass media? (No comments section, though, thankfully. Imagine the flamewars.)

It’s a damned good story. But maybe avoid checking Twitter after you read it.

Langan does an excellent job of invoking Mythosian horrors without naming them. Ransom has no way to know that this outsized horror is Cthulhu, that one Tsathoggua, and oh that’s a Shoggoth* over there eating your kid. He just knows that he’s surrounded by forces beyond his comprehension or ability to control. And in the face of all that, he’s going to keep his garden going. And talk to his sorta-crab. Like Matt and Heather, he’s going to keep fighting for life, in the little ways he’s capable of. Il faut cultiver notre jardin. I can appreciate that.

The monsters of “The Shallows” are cosmically horrible in many ways. They’re huge, inexplicable and unexplained, beyond the ability of humans to understand or fight. But they’re human-like in at least one way: they’re vindictive. Why else show Ransom, of all people, those particular scenes? Why send those particular apples to grow in his yard? Unless every survivor has rebel-faced fruit growing in their yards, it does make you wonder. After all, if you can get the giant inhuman force to notice you, maybe resistance isn’t so futile after all.

*For all that we hear a lot about shoggothim in the Mythos, they almost never appear in person outside “Mountains of Madness.” Langan’s version are a worthy on-screen addition.

Anne’s Commentary

To start on a personal note: The full name of the Albany complex where Ransom’s son meets his death is the Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza. It was indeed the brainchild of Governor Rocky, as my father fondly called him, designed to strike visitors to the New York capitol with awe as they flew in or crested the hills on the opposite bank of the Hudson River. Impressive it is. Also unsettling, especially against a flaming sunset. Architectural critic Martin Filler describes this aspect of the Plaza well: “There is no relationship at all between buildings and site…since all vestiges of the [previously] existing site have been so totally obliterated. Thus, as one stands on the Plaza itself, there is an eerie feeling of detachment. The Mall buildings loom menacingly, like aliens from another galaxy set down on this marble landing strip”

No wonder Langan chose this spot as the lair of shoggoths and their Master Toad (Tsathoggua?) Still, I have fond memories of sitting by the Plaza’s vast reflecting pool, watching Fourth of July fireworks duplicated on the glassy black water. And besides, Governor Rocky once gave my five-year-old cheek a big smack. Quintessential politician, he was an adept pumper of hands and kisser of children. We needn’t go into his other feats of osculation here.

“The Shallows” is my kind of post-apocalypse tale: up very close and very personal. John Langan addressed the aftermath of a zombie epidemic in “How the Day Runs Down,” a novella brilliantly structured like the worst-case scenario version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Here he takes on that greatest of all possible apocalypses, the return of Cthulhu and Company. In “The Call of Cthulhu,” Lovecraft (via cultist Castro) envisions that return as a time when “mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones, free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and reveling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom.” Quite a party, however (literally) burnt out the revelers were bound to feel the morning after. Langan’s vision is a much soberer one—no Boschian orgy of damnation but one man crucified, cross-affixed by the nails of his greatest fears, over and over again.

Langan’s Great Old Ones wreak mass destruction, sure, like that monstrous gray gash north of Ransom’s house. It looks like some huge hoof scuffed Earth’s skin to the rocky bone, stomped trees and roads and buildings, animals and people, indiscriminately out of existence. But the Old Ones aren’t merely mindless force. They seem to reserve some humans for prolonged, subtle torment. Ransom’s one such sufferer, stranded among light-curtain movie screens that endlessly replay not only planet-wide catastrophe but Ransom’s most personal tragedy: Matt’s violent death, only fifty miles into his quixotic journey north to the polar city. How do the “screens” work? Are they dimensional rifts disgorging alien flora and fauna to infiltrate terrestrial ecosystems? Are they also veils of some energetic fabric that serves as both broadcast medium and psychic sponge? Via the veils, all can witness R’lyeh’s rise and Cthulhu’s escape. Upon the veils, each survivor can “record” his individual horrors.

Cosmic-class bastards, the Old Ones. Unless the effect of the light-curtains on the human brain is accidental, the hallucinatory product of our own mental vulnerabilities. What about the screaming-Matt apples, though? Ransom himself doesn’t describe them to the reader—while we share his point of view, we only know the apple trees make him uneasy. It’s in the closing switch to authorial point of view that we learn what terrible shape the fruit’s taken, and that suggests to me that the new world order has deformed them, for Ransom’s particular anti-delectation.

Shades of a Color out of Space, by the way!

Now, what about the crab that is no crab, at least no earthly one? Nice parallel, how Ransom “adopts” it with as little apparent misgiving as Heather adopted the dog she named Bruce. I’d like to think the crab’s drawn to Ransom out of a mutual need for companionship. Maybe it’s a larval Mi-Go, hence both telepathic and highly intelligent, the child of Mi-Go tenders of vast fungal gardens on the mountain terraces of Yuggoth.

Speaking of gardens. As Candide tells Pangloss in the story’s epigraph, we’ve each got to tend our own, regardless of whether we live in the best of all possible worlds or the worst. Ultimately that’s the only way we can go on. Not through the heroics of a Matt, but through the grubbing labors of a Ransom. Do heroes seek heights (and, conversely, depths?) Are gardeners content in the shallows?

Oh dear, though, doesn’t Ransom tell us true when he says there are sharks in the shallows as well as the depths? Downer, if we take that to mean there’s no safety anywhere. But uplift, too, if we take it to mean both shallows and depths require courage of the swimmer, foster their own brands of heroism.

Next week we delve once again into Lovecraft’s juvenalia, and meet the angsty scion of a fallen line, in “The Alchemist.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

There’s a sort of Dickian feel to this. Fairly late PKD, too. I’ve seen a fair share of Lovecraft mashups — Kerouac, Hammett, Conan Doyle — but I don’t think I’ve ever seen one with PKD. Maybe they’re too close in ways that count and it would be hard to tell, but it might be something like this.

I never liked portrayals of apocaypse much, and like them even less now. But this one sounds pretty interesting. I prefer an invasion of deadly wildlife to obliteration of life. I would read it if any of my libraries had it, but they don’t.

This one somehow reminded me of Murray Leinster’s Sideways in Time, not so much because of the plot or theme, but because of the evocation of a patchwork quilt reality resulting from an apocalyptic, or potentially apocalyptic, event. Looking a few hundred yards away and seeing an alien forest with unfamiliar life forms is pretty unsettling, even if Leinster didn’t use the trope to evoke horror.

I also took his answer about staying in the shallows to mean that life is dangerous everywhere, but also it seems to imply they’ve adapted to THESE sharks. In that vein, this story reminds me of The Road or A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. The latter in particular, which is about a man in a Russian labor camp. But while it highlights the hardships of living in such a place, Ivan is used to it all and in fact a few decent things happen. Granted, he has a hope of release and returning to his family later, unlike Ransom. They share a similar sense of “I’m surviving because I must and what else am I supposed to do?”

On another note, I question the reliability of these movies. Why do the Elder Gods et al care about finding one old man and showing him his son’s death? Sheer cruelty of course, but that sounds like a lot of effort for one guy with zero motivation to stand against them. To me it makes more sense that some local entity wants to depress and/or frighten Ransom by showing him horrifying things, whether they’re true or not. This would also be useful if the various gods and things were warring and you wanted the humans to think they were one horrific united front. Elder God propaganda.

Hi

Great choice, Cthulhu’s Reign is one of my favourite Lovecraft themed anthologies. My favourite story in it is Will Murray’s What Brings the Void but I also enjoyed The Shallows I have been readings all of Langan’s work I can find, I like Langan’s approach, which was often quite unexpected. Not just in his novel The Fisherman but some of his short stores like Anchor in Autumn Cthulhu or especially Outside the House Watching the Crows, Mammoth Book of Cthulhu. Like Ruthann I enjoy end of the end of the world stories that are so common in SF (John Wyndham fan here). I also like the fact that Ransom does not have a book, old or reprint, HPL t-shirt or DVD of Dean Stockwell in the Dunwich Horror, instead we get a view of Ransom’s family, his wife Heather, son Matt and the crab’s namesake Gus. He doesn’t really know who these critters are only that they spell trouble and a new reality. The action, Matt’s journey, the dispatching of the lobster-like things are almost peripheral to Ransom’s viewing of the curtains/screens and patrolling the garden. Langdon’s introduction of the crab Gus gives the story an almost Boy and his Dog vibe on a post-apocalyptic future. I liked most of the stories in the anthology and Langan’s is one of the best, in many of the stories the people don’t really know the players or what it means, only that they are trapped in some horrible new reality which will not be forestalled by several professors with a chant and a garden sprayer. I also really enjoyed Anne description of the Empire State Plaza she really brought it to life for me. For me this was cosmic horror. I am really enjoying the re-read.

All the best.

Guy

Miscellaneous thoughts:

– Could “Ransom” be a nod to C.S. Lewis’s protagonist?

– I feel like I’ve seen the word “shallows” used before in the context of zones of cosmic weirdness, but I can’t remember where? Anyone know what I might be thinking of?

– I haven’t read this story, but from the synopsis, I wondered if the apple tree might be psychically responding to Ransom’s thoughts.

– The plural of apocalypse is apocalypses. (Incidentally, I heartily approve of the adoption of Stross’s “shoggothim” as the plural of shoggoth.)

Reader Chris Collins was kind enough to share this photo of Albany that he snapped while living there. Hardly needs a toad god to set the mood…